Will be forthcoming in Adelaide Literary Magazine 2020 Essay Anthology

Every day as the statistics for the Coronavirus become more alarming and as my previous life becomes increasingly more distant, as I sit in the persistent California coastal sun, I can feel my conflicted Iberian, Amazonian, African and Indigenous bloodlines becoming daily more awake.

I feel it in my appetites—for coconut, banana, for rice and black beans, as well as in my aesthete preferences. I want to hear percussive jazz, fados, the samba and the Bossa Nova, and I want interiors with clean beach lines and splashes of continuous color. I dream of parrots and macaw.

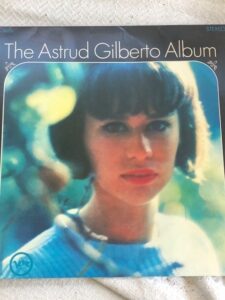

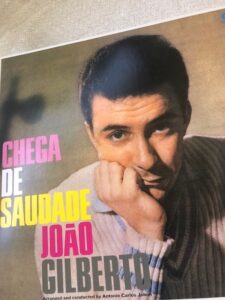

Because the virus looms and we cannot really go out (save into my hibiscus and jasmine filled small yard where the scent of rosemary hangs heavy, or to walk on the beach sand packed firm by record high tides—I grant you, quite a magnificent exception), I order things. I pore over just delivered cookbooks (once they’ve been properly decontaminated) and study the recipes for coconut and avocado cream and for the Brazilian national: dish: feijoada. I buy a day-glow colored sundress and pillows woven from saffron, melon and orange hued fabric. I listen habitually, nearly obsessively, to my record albums featuring Sergio Mendes, Joao Gilberto, Antonio Jobim, Stan Getz and Charlie Byrd.

I want my mother.

Now, fifteen years after her death, when nearly all of our old allies and relatives in Brazil have slipped away, now when it’s far too late to please her, I feel my long repressed Brazilian self rising to the fore.

How does one become Brazilian?

I study Portuguese now, and listen to the vinyl voices for traces of my mother’s voice. I examine histories, poetry, and once again read about the Two Husbands of Dona Flor.

It’s a matter of soul, my mother would say.

Like so many of my generation from immigrant parents I grew up wanting normality above all. My parents were eccentric (to say the least) and my mother’s English was strongly accented. My mother didn’t know how—or refused the knowledge—of how to make ordinary school lunches. She wore expensive knit dresses and shirts that tied at the waist to just sit around the house. She had no interest in the parent teacher groups at my school, or in camping or entertaining my father’s colleagues from work. When all of the other mothers at my school wore their hair in little bubble cuts my mothers curls fell to her shoulders. She would move around the house dancing (again, embarrassing). She never gardened.

I wanted straight blonde hair like a surfer girl. I wanted to be both the most popular and exactly alike every other girl. I was serious while my mother was perpetually light of heart.

I wanted to fit in.

And although my mother was not above making an acidic remark if some stranger commented on her immigrant status (going to some length to say that she here not by choice but because my father insisted and that her Brazilian life was far grander) I think she too secretly longed for a bit of anonymity.

While other families huddled together on Friday nights eating tuna fish and potato chip casseroles, my mother entertained. She located every Brazilian within the vicinity—retired party girls, an evangelical preacher, international college students, a Marxist musician along with a classical piano player, as well as a professor of Hispanic and Iberian literature. She would seat the refugee White Russian and his Hungarian wife next to an American engineer and inventor married to a wife nearly thirty years his junior. A plump American lady with died red hair who was exiled from the local Women’s Club also joined their group, bringing with her a trim if tiny husband with a ferocious mustache and her blonde aspiring actress friend who once got a role in a commercial for television. A sculptor from the nearby Padua Hills was an occasional visitor and there was an American couple studying Portuguese for a sabbatical year in Brazil. A balalaika came into play, along with a weird gourd equipped instrument introduced by my mother. She served olive stuffed empanadas and coconut pudding and tiny cups of black sweet espresso.

I hungered for average, but now I have a hunger that cannot be abated.

My mother’s best friend Laice visited when I was in high school. She and my mother walked arm and arm to the liquor store to buy cigarettes. I worried about what people might think. Once long ago when we lived briefly in New Jersey my uncles visited and took us out for dinner in Manhattan. My uncle bribed the band to play a Frank Sinatra song and then did a samba variation with me around the dance floor. In those years there were suitcases filled with dolls and candy and canned sweet paste made from guava. Goiabada. I can taste it now. (My mother made sheet cake in a jelly roll pan. She rolled the cake and cooled it and filled it with jelly.) Later there were other gifts: a parrot made from jade, a gold bracelet bearing my name, feathers and a stuffed monkey. Again I was nearly frightened by the exuberance—a kiss on each cheek even if I simply returned from the store, long embraces and invitations to visit for a week or a month or a year. Or even forever.

It was too much.

Or so it seemed. Now I labor over a recipe for Manjar Branco com Ameixas e Coco, translated roughly as the Eyes of the Mother-in-law. I omit the prunes from the directions. I make my mother’s cream puffs and serve steak a caballô to my spouse.

Food is the stuff of memory.

Black beans. Rolls stuffed with cheese.

Emerging from a messy divorce I took my mother’s name in place of my former husband’s. I loved my father but I was sick of men’s names, sick of that tag of belonging. I wanted my own new name—not something left over from childhood, not some new man’s surname. I wanted my own.

I never went to Brazil. It’s a long story why—tensions between my parents, between me and my mother and then between my father and I. These days I’m afraid of air travel. Maybe it’s better that way (although I doubt it). Brazil was the liminal space, that place of emotion and dance.

When I was in college I was amused to discover that lots of people feel this pull. Thomas Mann writes about his Brazilian mother and Germanic father. For Mann, Brazil represents art, yearning, love, the id, music, three free self. The father is a merchant. His pull is toward order, law, rationality, the way things are supposed to be. Thomas Mann’s mother had blue shadows under her eyes. I see them on my own face,

My father was an engineer. He never learned to dance.

As the years pass by I walk arm and arm with my own girlfriends and share an abraco with everyone.

I used to say my taste was Mediterranean. I said my home was on the Riviera of the Pacific (California’s Central Coast). Then I substituted Iberian.

Now nearly ten thousand miles away from my mother’s city I finally claim my own identity. I am Brazilian.

Or, I am becoming Brazilian.

Nana nemen

Que a cuca voi pagar

Mamae foi pira roca

Papai foi trabalhar …

Serra, serra, serraado

Serra o papo do vivo…

The translations for this first lullaby are, roughly speaking, go to sleep, there’s a monster lurking. The other set of lyrics concern the sawing off the neck of the old grandfather. I remembered the words when I had children of my own.

Like my mother I like china and chocolate. I like music and company. Serra, serra,serrado….

Here in quarantine there is little socializing.

My husband and I go on long drives. We walk the beach.

One night when grief and fear seemed too much I swear my mother came and sat on the bed by me, rubbing my back until I slept.

One late afternoon not too long before her death I took my mother for an outing. We went to the mall. She bought a blue Italian knit suit. We had lunch (she ate fruit and the top of a muffin). At home after a walk I lay down for a nap while my mother rested. I woke to find that she’d covered me, made tea and a (vegan) sandwich for me. I can still take care of you, she said.

Majolica pottery. The music of Heitor Villa-Lobos. Carnival. Sun. Hearts of palm served with black olives. The big rocks at the mouth of the harbor here. My legs stretched out in the light.

The Girl From Impanema. However cliched. Over done.

These are the words that I know.

These are the writers, Armado and Machado. Philosopher or Dog?

There’s no t-h sound, like in this or the. Just the soft sh sh sound of Portuguese.

Sh sh shhh like the sea.

My mother grew up two blocks from the water.

Shhhhh.

Bela Horizonte. Rio de Janiero. Curtiba. Porto Alegre. Santos.

The old house was razed to make way for apartments. My aunts lived in a glossy compound a few blocks removed. Unlike my uncles, they never married.

My mother grew tall. Swam in the sea. Walked on the shore with her sisters. She sang a song about Clark Gable. Clark Gable, Clark Gable. Take me with you to Hollywood. The real girl from Impanema.

Shhh. Shhh. Shhh.

I am cooking rice and beans. The beans are multi-colored—red, tiger eyed, of course, black.

I listen to music. In an hour or two I will walk down by the water.

In the meantime I’ll memorize a new list of words.

Melancolico. Lamentavel. Triste.

Sabedoria. Prudencia

Velha.

Antigo.

Amarela. Azul. Verde

O ceu, o mar.

Shhh.

Mama, I am becoming Brazilian, like you.